Articulating the Cost of Inaction

As the coalition came together, it was clear that we would have to summon both the public will and resources necessary to tackle this growing crisis – which posed a challenge in a community facing a number of serious needs.

So, early in their journey, the coalition launched an effort to gather a full picture of the cost of homelessness in Santa Clara County. This was one of the first times that such an endeavor had been undertaken, and it required the effort of several key partners. Destination: Home served as the sponsor of the project and hired the Economic Roundtable – a nonprofit, public benefit corporation conducting applied economic, social and environmental research – to serve as the lead researcher. In addition, the project was underwritten by the County of Santa Clara, which also helped the coalition navigate and overcome significant barriers and legal hurdles in order to assemble a systemwide view of costs.

As part of this project, researchers ultimately looked at records for more than 104,000 homeless individuals who had interacted with a County agency at some point between 2007 and 2012.

In 2015, the Economic Roundtable published its final report titled “Home Not Found: The Cost of Homelessness in Silicon Valley.” This study was the largest and most comprehensive body of information assembled in the U.S. to analyze the public costs of homelessness.

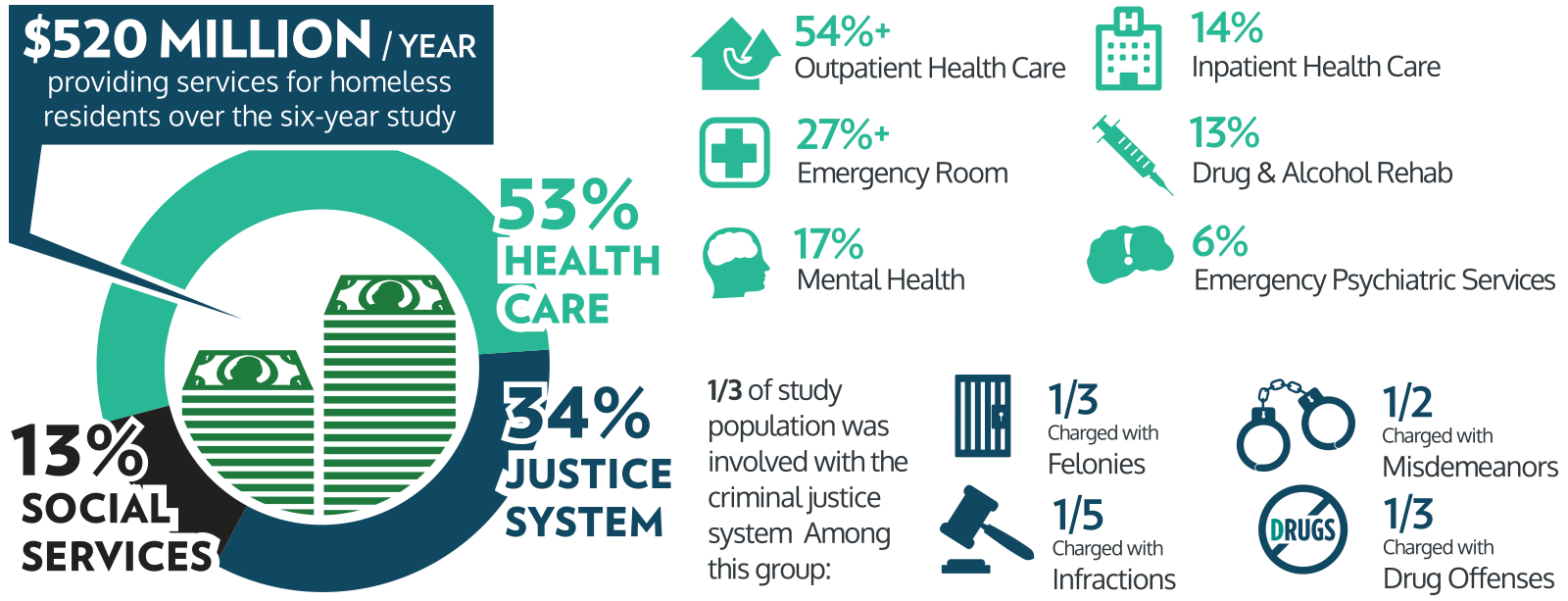

This study revealed a startling fact: the County of Santa Clara was spending a staggering $520 million each year responding to the needs of homeless residents without actually resolving their homelessness. The majority of these costs were in the healthcare system (including outpatient care, emergency room visits, and mental health services). Researchers also found that these costs were heavily skewed toward a relatively small group of high-need individuals.

“Home Not Found” also shed light on the potential cost savings associated with expanding a Housing FirstThe Housing First approach prioritizes providing permanent housing to people experiencing homelessness, thus ending their homelessness and serving as a platform from which they can pursue personal goals and improve their quality of life. This approach is guided by the belief that people need basic necessities like food and a place to live before attending to anything less critical, such as getting a job, budgeting properly, or attending to substance use issues. The Housing First approach has been validated by numerous rigorous studies — with evidence indicating that, compared to a “treatment first” model, it leads to greater long-term housing stability. approach, specifically for chronically homeless people.

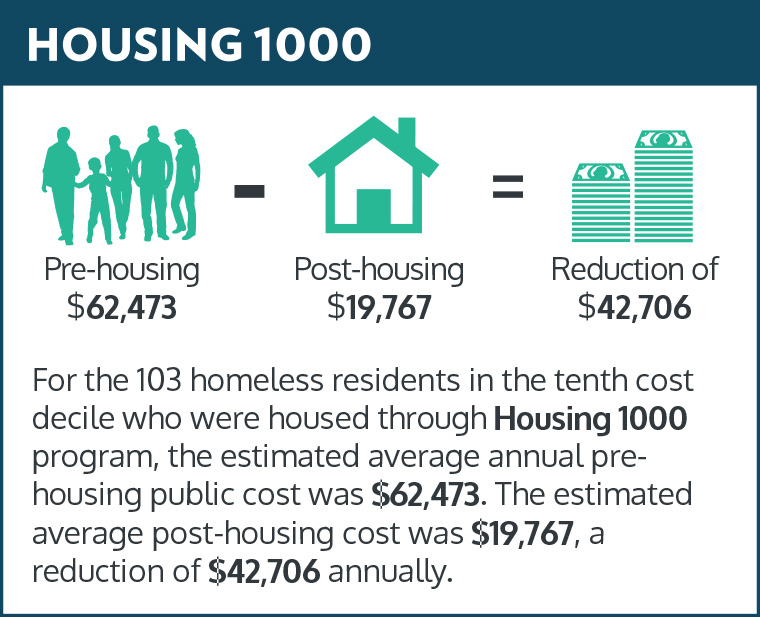

For example, looking at a subset of individuals housed through the Housing 1000 campaign (those with the highest usage of public services), the results were striking. While they were homeless, the County of Santa Clara provided $62,473 in average annual support services for each individual that did not solve their fundamental need for housing. However, once these individuals were housed, the County’s average annual expenses per person dropped dramatically to $19,767 – a reduced cost to taxpayers of $42,706 per person per year. While these amounts may differ across other demographics, they are indicative of the potential for cost savings via a Housing First approach.

By putting clear dollar amounts on the costs of homelessness versus the cost of housing, “Home Not Found” underscored the limitations of treating only the symptoms of homelessness. It also undercut many common objections to spending money on building more affordable housingSubsidized housing where rents are set at a below-market rate based on the tenant’s income. There are many different types of affordable housing — units are typically designated based on a tenant’s income level (i.e., low-income vs. extremely low-income) and certain types of affordable housing may also be reserved for a specific demographic (i.e., seniors or veterans). Deeply affordable housing refers to developments or units where rents are kept particularly low and are intended to serve the lowest-income residents in the community. options. And it ended up serving as a major catalyst for securing key sources of new funding and catalyzing bold investments to end and prevent homelessness throughout Santa Clara County.